TURIN, Italy – The Italian artist Salvatore Mangione, known as Salvo, was born in Sicily in 1947, but moved with his family to Turin in 1956. There he remained – apart from several trips – until his death in September 2015. In the Piedmont capital he showed an early interest in art, and in the late 1960s he attended Turin’s artistic scene in the most stimulating years for the art in the city.

He met the Arte Povera artists including Mario Merz, Gilberto Zorio, Giuseppe Penone and Alighiero Boetti, who, like Salvo, traveled to Afghanistan. He frequented the gallery of Gian Enzo Sperone and critics like Germano Celant, Renato Barilli and Achille Bonito Oliva.

His research, however, differed from that of Arte Povera. In the early years of his artistic career, in fact, the main issues relevant to his art emerged: the representation of self, the pursuit of the ego, narcissism, and his relationship with the past and the history of art. Among his earliest works were self-portraits in which the artist superimposed his face on the images of the newspapers – as a soldier, a worker or a dancer. In some works, he writes his name across the Italian Flag or on images of books, replacing the names of literary protagonists with his own. After these first photo-montages, presented in 1970 at the gallery of Gian Enzo Sperone, he presented at Acme Gallery in Brescia some works in which he blesses the city, ironically referring to Christian iconography. One of these works, the Blessing of Lucerne, is now at the Kunstmuseum Luzern.

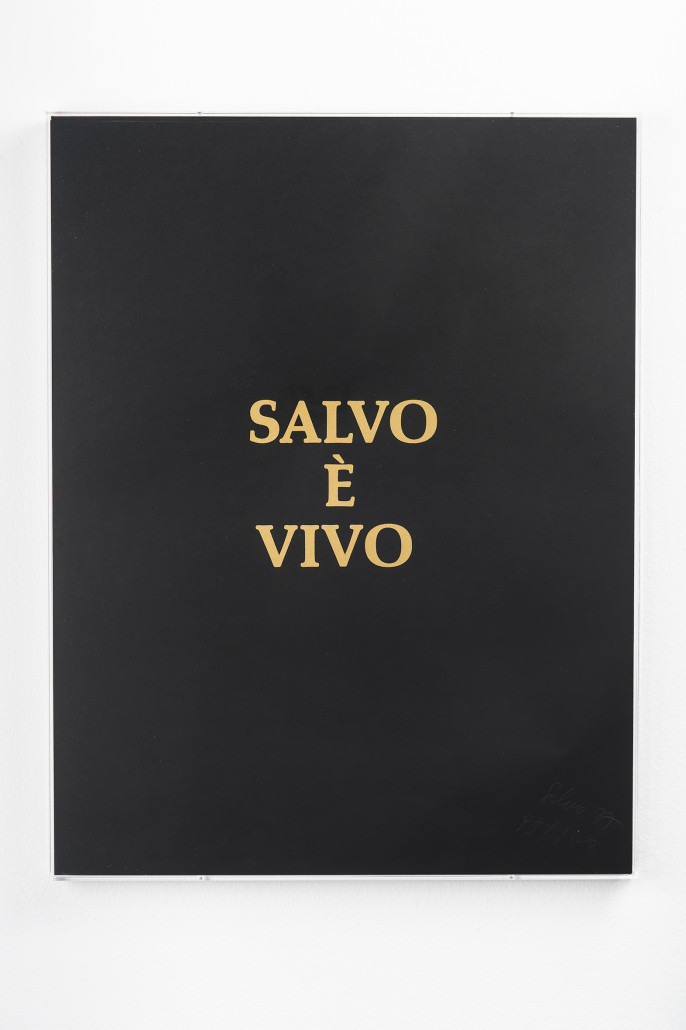

Alongside these collages, he started working on tombstones on which he engraved sentences like “Salvo lives” (now at the Australian National Gallery in Canberra), “I’m the best,” or a series of 40 famous names from Aristotle to Salvo himself. In 1971 he showed at the gallery of Paul Maenz in Cologne and Yvon Lambert in Paris, both of which were important to the furthering of his career. The following year he exhibited in New York at the gallery of John Weber. He also participated in Documenta 5, and showed at the gallery Art & Project in Amsterdam.

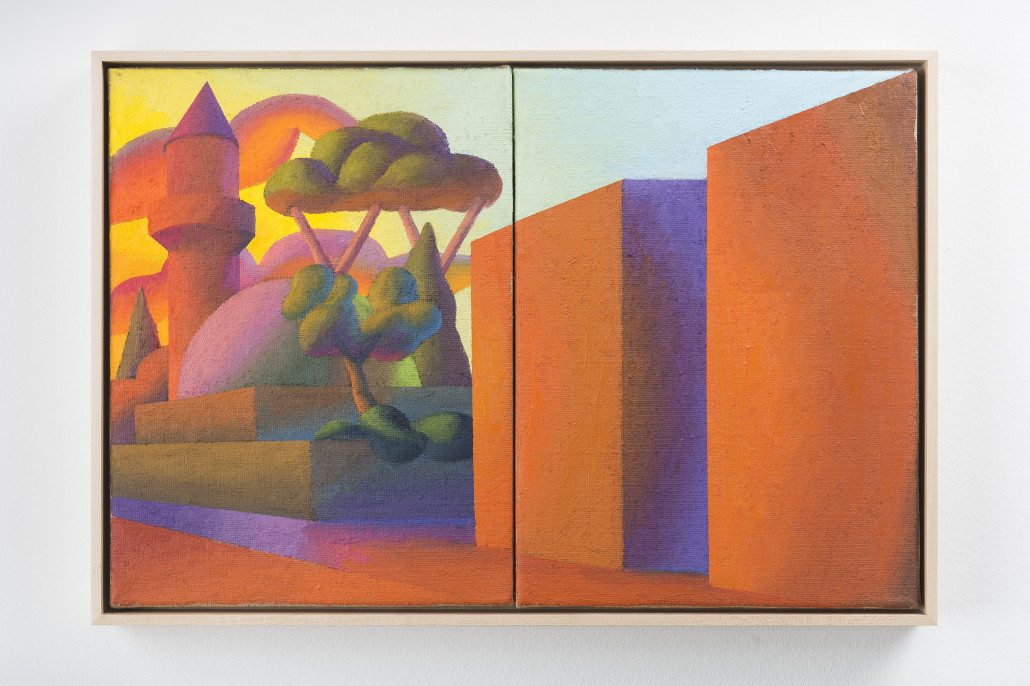

But here is where one encounters the end of the Salvo’s conceptual period. Beginning in 1973, he returned to painting with works inspired by the masters of art history – a series started in 1970 with his self-portrait as a Raphael. In this period he conceived the works inspired by the masters of the 15th century — revisited with simplicity and naiveté — exhibited at the Tonelli gallery in Milan in 1973. In 1974, at the show “Projekt ’74,” he asked to exhibit his works at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne next to a masterpiece by a painter for each century, from Simone Martini to Cézanne. In the same year he exhibited a 7-meter painting with the Triumph of St. George (by Carpaccio) at the Toselli gallery. Later, in 1976, he exhibited the same work at the Venice Biennale. He also exhibited at Studio Marconi in Milan and at Banco, Massimo Minini’s gallery in Brescia.

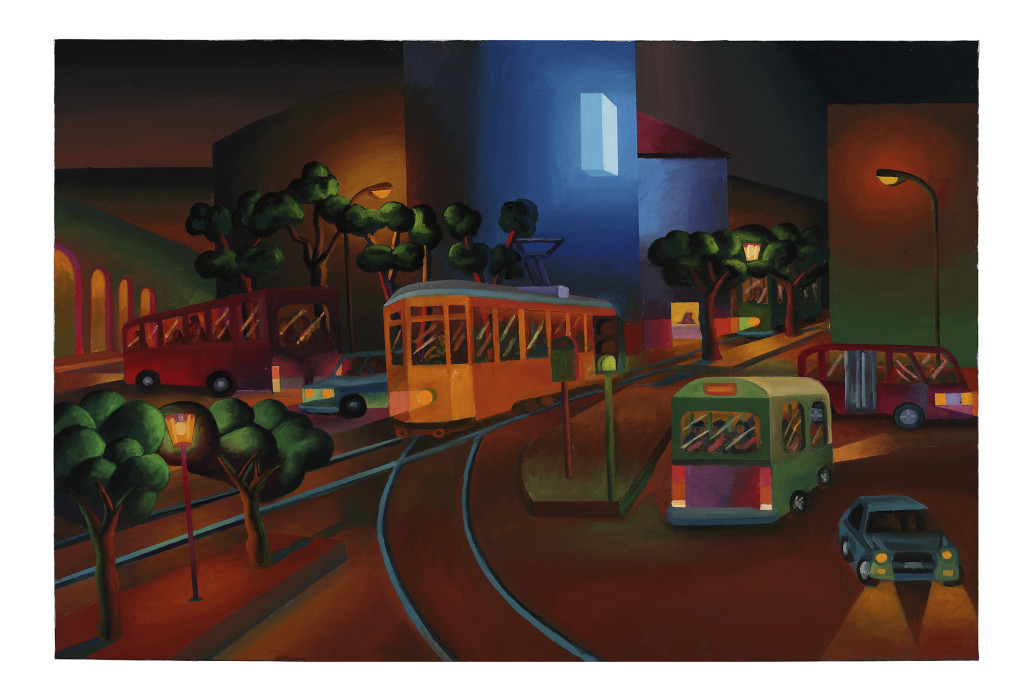

During these years he started the series called “Italie” and “Sicilies,” simplified maps with the names of painters, philosophers and musicians. Beginning in 1976, Salvo developed a new creative phase, which was dedicated to landscapes characterized by simple, geometric shapes, colors that over time became more shrill. His depictions included knights, architectural ruins, fairy-tale atmosphere, and classical columns, represented at various times of the day. Over the years, Oriental landscapes also became frequent, as did minarets, derived from his travels in Asia. Since the end of the 1970s, Salvo has exhibited in Italian and international museums, including the Museum Folkwang in Essen and the Mannheimer Kunstverein in Mannheim. For the entire period spanning the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s he had frequent shows both in Italy and abroad, in galleries and museums.

In the last 25 years, his landscapes and still-life artworks frequently have evoked the passing of time, of the seasons and of the months. From 1995 to 2007 he spent several months a year at the foot of Monviso, a place that inspired many of his works. From 2005 to 2007, however, the valleys of his landscapes gave way to plains, and he introduced new cuts in perspective. A trip to Iceland in the summer of 2006 became a starting point for a series of paintings. In 2007, Salvo had a major retrospective at the GAM in Turin, and since 2008, Salvo has spent a considerable amount of time in the area between Langhe and Monferrato, whose rolling hills appear in his works of recent years. In 2013, he started working with the gallery of Mehdi Chouakri Berlin, where he had his first solo show a year later; and with Mazzoli gallery in Modena, where he exhibited for the first time in 2015.

His daughter, Norma Mangione, has carried on her family’s fine-art legacy. She is an art dealer in Turin.

___

By SILVIA ANNA BARRILÀ